I started a SpriteKit series on App-o-Mat

Author Archives: Lou Franco

Beating the Market Addendum: Taxes

A few days ago, I wrote about how programmers can beat the market in their investments.

The key is to invest in yourself and either increase your value in the labor market or sell products. If you think of the extra income you earn as “market return”, then you can easily add a few percent to your overall return with minimal risk of downside.

But the astute among you might have realized that income is tax disadvantaged vs. capital gains (from stock returns). And, that if you buy and hold stocks, then you can defer taxes. But if you make income, you need to pay taxes immediately.

And since I am advocating you getting side income or raises, this extra income is at your highest income tax bracket.

DISCLAIMER: I am not a CPA or financial advisor and even so, it is May 2021, so everything I am saying is possibly not true if you are reading this in the future. Also, this is US only. Check with your accountant to see what the effect is to you personally. Also, I am intentionally simplifying some things because the actual tax law is way more complex than this.

Also, my original article and this one assumes you are a programmer, which is why my salaries in the example are 100k and over 140k. A lot of this math doesn’t work unless your salary is in that range. At lower income, long term capital gains tax is 0%.

For this analysis, I am assuming you are single. The numbers are different if you are married, but the idea is the same.

Here’s an example:

Let’s say you make a salary of $100k, and you get $10k of extra income. If you are single, that $10k has federal tax of about 24% and FICA of 7.65% (you may also have state taxes). If you get this money via consulting or selling products, you pay another 7.65%. The total rounds up to 40%. (BTW, I know it’s more complicated than this, but this number is approximate)

But if you buy and hold stocks that go up an extra $10k over the market, your tax bill is $0. You only pay tax if you sell stocks. So, eventually, when you do sell them, it will probably be 15% long-term capital gains. Again, it’s more complicated than this, and in 2031, when you sell, who knows what the tax law will be, but 15% is our current best guess.

So, of the extra $10k, you keep about $6k if it’s side income, $6.8k if it’s a raise, and eventually $8.5k if it’s market gain.

Now, if you day trade stocks or bitcoin and don’t hold your positions for a year, then the gains are taxed at the same rate as wage income, so 24% in our case (no FICA). So you keep $7.6k instead of $8.5k.

You still pay less tax trading, but the good news is that it’s not that simple.

I’m ignoring state tax, because mostly that’s a wash, but you need to check because in Massachusetts, short-term gains get taxed at 7% more than wage income (12% vs 5%). I live in Florida, which doesn’t tax income or gains. So, it could make a big difference depending on where you live.

The biggest tax savings are from maxing out your social security tax.

I used $100k base salary, but in 2021, if you make $142.8k, you max out your social security tax and only pay the Medicare portion on your side income, so that’s 2.9% instead of 15.3%. Your tax bracket is about the same, so now you pay 27% of the total vs. 24% for a day-trader. If the new income is a raise, then you pay 1.45%, so a total of 25.45%.

If your new income is a raise, you can further lower your taxes by increasing your 401k (or other tax deferred) contribution. If you get a $10k raise, and can put all of that in the 401k, then your tax rate is 1.45% for Medicare.

To be fair, as long as you have enough wage income, you could effectively do this with your market return by contributing the equivalent amount of wages, so it’s a wash. But I want to mention it because it’s the first thing you should consider doing with extra income no matter how you get it.

If you make the money on the side, you can lower your taxes in ways that don’t apply to market returns.

There’s a QBI deduction of 20% on net business income. So, you only pay tax on $8k of the side income. So it’s an effective rate of ~22%.

Now we just beat the day traders who pay ~24%.

But what about the stock pickers that buy and hold? We still have to make $11k for each $10k they make (again, that’s not hard).

Even if you max out your 401k, you can put 20% of your net business income in a solo 401k (or other business tax deferred vehicle).

So, if you make $10K, you could put $2k in the solo 401k, deduct $1.6k (QBI) and only pay the 24% tax on $6.4k and another 2.9% on the $10k. So your effective take-away is about $8.2k, with an effective tax of 18%.

Remember, this is all approximate, I am not a CPA and there are more things to take into account. For example, you eventually pay tax in retirement on the money in the 401k.

Also, I didn’t take any normal business deductions into account, like home-office, computer, tech books or courses, business group membership fees, etc. If you can deduct about 5% of the income, your effective tax rate on the side income is lower than 15%.

But the takeaway is that you can get your tax bill in the same range of the day traders with extra wage income if you already max out your Social Security contributions. It’s not as tax-disadvantaged as it seems at first.

The traders pay something between 15%-24% depending on how long they hold, and you pay something between 18% and 27% if you max out Social Security at your day job. And you can get it even lower with business deductions.

You do need to add another 12.4% if you don’t max out SS—so go get a raise to get you closer to maxing out.

Of course, you lose the option of negative tax that comes from stock picking losses, but we can live with that.

Write While True Episode 10: Finding My Why

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

The exercise this week is to think about your “why”? I don’t think it’s wrong to write for money or fame, but if you’re an amateur like me, I’d find something easier to attain.

Using Market Data in the Python Net Worth Estimator

When I first made the python version of the net worth spreadsheet, I used a function like this:

def netWorthByAge(

ages,

savingsRate = 0.18,

startingNetWorth = 10000,

startingSalary = 40000,

raises = 0.025,

marketReturn = 0.06,

inflation = 0.02,

retirementAge = 65

):You could pass in parameters, but only constants. This is how the spreadsheet works as well—each cell contains a constant.

The first thing to do to make it more flexible is to use a lambda instead for the marketReturn parameter:

marketReturn = (lambda age: 0.06),Then, when you use it, you need to call it like a function:

netWorth = netWorth * (1 + marketReturn(age - 1)) + savingsWe use last year’s market return to grow your current net worth and then add in your new savings.

The default function is

(lambda age: 0.06)

This just says that 0.06 is the return at every age, so it’s effectively a constant.

But, instead, we could use historical market data. You can see this file that parses the TSV market data file and gives you a simple function to look up a historical return for a given year.

Then, I just need to create a lambda that looks up a market rate based on the age and starting year:

mktData = mktdata.readMktData()

for startingYear in range(fromYear, toYear, 5):

scenario = networth.netWorthByAge(ages = ages,

savingsRate = savingsRate,

marketReturn = (lambda age: mktdata.mktReturn(mktData, age, startingYear = startingYear))

)And this will create a scenario (an array of doubles representing net worth) for each year in the simulation.

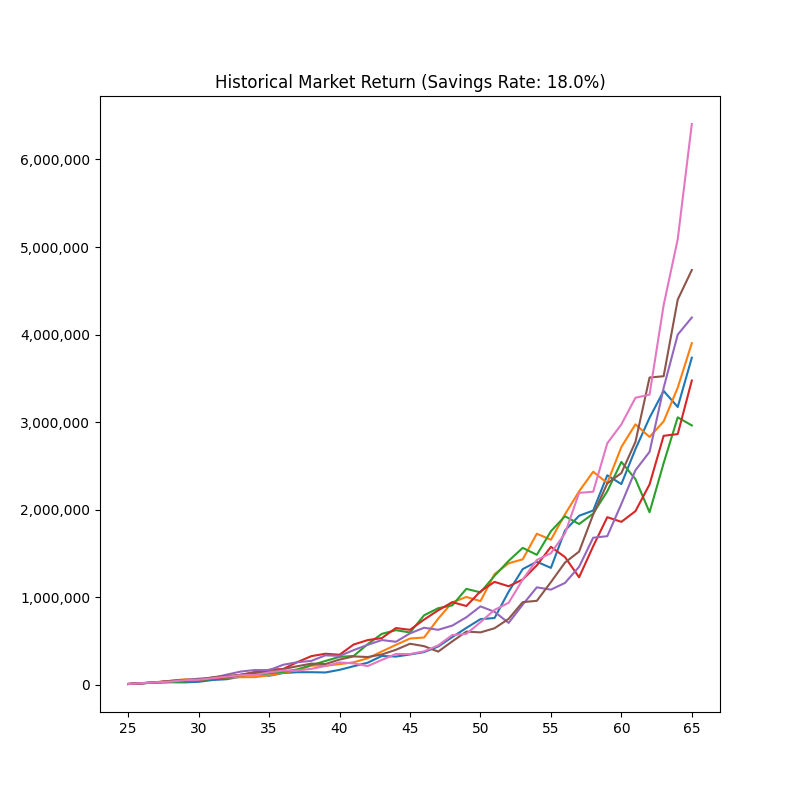

You can download and run the code to play with it. Here’s a sample chart it generates:

There are lines for starting the simulation in 1928, 1933, 1938, 1943, 1948, 1953, and 1958. This gives you an idea of the expected range of possibilities.

How Programmers Can Beat the Market

In my last few posts I’ve been trying to model net worth over time as a function of savings. In my last post, I used real historical market data instead of a constant 6%. Looking at a few scenarios, the market returned more like an average of 9.5% over those time periods.

I still think you should use 6% in your plans (if it’s actually 9.5% in the next 60 years, then that’s good news—you can make adjustments every decade if you are way ahead of plan).

Reminder: I am not a financial advisor and this is not advice. I don’t know anything about your personal situation. Talk to a fiduciary if you want advice.

But, you might think: “I bet I can beat the market—I understand tech/bitcoin/stonks better than most people.”

It’s not likely.

S&P keeps a scorecard of actively managed funds against their benchmarks. In a single year, active funds may do ok against the market, but go to page 9 and look at their longer term performance. 75% don’t beat the S&P 500 over 5 years, and 94% don’t beat it in 20.

These are funds with professionals with a staff who spend all day, every day thinking about this and are paid based on performance. You can beat 94% of them by just putting your money in an index fund.

But, then what do you do with all of that free time?

To beat the market, remember that you are also a player in a market. If you work full-time, you are in the labor market. You could also create products and sell them (in the market).

Look at your current net worth. To pick a random number, let’s say it’s currently 100k. If the market returns 6%, you’ll have 6k more at the end of the year. If you try to beat the market by picking stocks, and get 10%, you have made $4k more. Let’s say your net worth is $500k. Working to get that 10% return will get you an extra $20k.

Is this really the best way to make an extra $4-20k? It’s not a sure thing—you might not beat the market (like over 50% of active managers each year). You could lose money.

So, instead, invest in yourself.

To “invest” in the labor market, you could take courses to make yourself worth more and then either ask for a raise or change jobs. You could raise your profile with an open-source project, writing, or by giving talks. You do not need to be “famous” to do this. Your projects or work don’t need a million followers. You could beat the market with a few dozen.

Outside of your job, you could seek side-income. If you make $100/hour, you only need 40 hours of consulting (less than 1 hour/week) to “beat the market”. Technically, you beat the market in your first hour.

Or with your first sale.

And there aren’t a lot of costs to consulting, e-books, or software (other than your own time). But, at least you know that the time spent will net a positive return. Even if you make no sales, it’s pretty likely that you have made yourself more valuable.

If you spend 40 hours and make $4k in the market, that’s a one-time effect. You haven’t made yourself more valuable, and it’s unlikely you can do this year after year. If you get a $4k raise, your salary is $4k higher the next year too. Beating the market is automatic and you can build on it.

More good news: the less you money you have, the more “return” you can make this way. If you have $10k in the bank, making $10k on the side doubles your net worth. Getting a $5k raise is like a 50% return.

You can’t beat that picking stocks.

Adding Market Data to the Net Worth Spreadsheet

I found some historical market data on an NYU business professor’s home page. I put the first four columns on a new sheet in the Google sheets version of the net worth estimator.

I also put a sample portfolio that you could play with. It’s 70% stocks and then a mix of bonds.

Then, on the main sheet, I use the portfolio return column instead of the fixed 6% return.

Historically, a portfolio like that returned more than 6% — more like 9.5% on average. I showed three lines, one for starting in 1928, one for 1948, and one for 1958. Since I am trying to simulate 60 years, that’s about as late as I can can start. But, for planning purposes, being conservative is still a good idea in my opinion (which is worthless as I am not a financial advisor and this is not advice).

There are many things wrong with this model that I’ll address soon. The main issue is the the post-retirement spending model seems way too low. I am also using a constant inflation rate instead of historical data. Finally, wage inflation has not necessarily kept up with inflation, and certainly in down market years, we could expect wage freezes or temporary unemployment.

All of these things are a lot easier to model in python.

FIRECalc only simulates net worth after retirement, so it can do many more simulations (because of the shorter duration). Still, there are more than 40 possible scenarios in this data.

Next, I’ll add this data to the python version and try to draw more scenarios.

FIRECalc

In my net worth estimation spreadsheet, I used 6% as a default market return and recommended that you keep it conservative. If the market happens to be better that that, that’s good news. If you estimate it too high, then you might not save enough.

Another way to model this is to use historical market returns year-by-year.

The site FIRECalc does this for understanding post-retirement spending vs. expected market growth. It takes your portfolio size and starting expenses as input and then draws a line on a graph for each possible retirement year using real market data. You get an idea of what would have happened in all possible historical scenarios and what percent of the time you would not have had enough in your portfolio.

If you want to do a more sophisticated analysis, there are advanced versions on the site. For example, it assumes constant (inflation-adjusted) expenses, but if you want to do something more sophisticated than that, it offers a few spending models. You can also adjust your portfolio stocks v. bonds balance.

Doing this kind of analysis is the kind of thing that’s fairly easy to do in a program, but not as easy to do in a spreadsheet. It’s not impossible, but you would need a couple of columns for each scenario. In my version, to show 30 different saving scenarios, I need 60 columns, plus a few columns for the actual historical data.

I’ll work on updating the spreadsheet to show a few scenarios to give you an idea.

My Second Lesson in Personal Finance

Last week, I wrote about the first lesson that made a big difference in how I thought about personal finance. Namely, that savings rate is a big driver to outcomes, and that it is very much in your control. Along with that is the binary outcome of whether your savings grow or shrink in retirement and the divergent net worth results you will have as a result of that.

The next big lesson I got was from reading Ramit Sethi’s I Will Teach You to be Rich [amazon affiliate link]. By the time I had read this (I was 39), my finances were pretty much in order, and most of the book was more of a reinforcement that I was doing the right thing. It’s also a very entertaining read.

However, I did get one thing—a change in mindset to focussing on income over expenses to increase savings.

Look at the Net Worth spreadsheet. If you set it to a fairly high earner, say 100k to start and a savings rate of 20%, then at 39, they need to save around 28k.

This is aggressive. It would be hard to do much more. If you pay 30% for taxes and 25% for rent, you only have 25% left for everything else. It’s hard to imagine that you could find another 10,000 in savings.

But, finding another $10,000 in income is really not that hard for a programmer.

The book (and his site and blog) give many examples, but simply asking for a raise is probably the simplest and most likely to work. If you get into a habit of renegotiating every year, the combined effect compounds.

His other suggestion is side income. If you are a programmer, there are many ways you could do this. I tried many things over the years. In order of income success:

- Advisory consulting on software projects

- Programming side-gigs

- An Excel add-in

- Tutoring/Coaching programmers (I mostly do this for free, but I charged people that could afford it or where their company paid)

- Writing a book

- Writing for Smashing

- Add-ins for niche software (including for a future employer)

- iOS Apps (they are all free now, but early App Store was more amenable to paid apps)

- iOS Skillshare classes

Over my career, I made significant side income directly from this, which I mostly saved. In addition, many of these things directly altered the course of my career and led to better jobs.

For example, writing apps led to getting a book deal and becoming an iOS programmer with at least some credentials. That helped me get consulting gigs when I did it full-time (or on the side) and was a factor in getting hired by Trello (along with, possibly, the add-ins I made for FogBugz and CityDesk).

The Net Worth Spreadsheet in Vanilla Python

This article is based on the spreadsheet I made to estimate net worth over time.

I think that Excel is basically a programming language, and I have an interest in bridging the gap from it to more traditional languages. And I needed an excuse to get matplotlib working on my machine.

Luckily, procrastination worked in my case. If I had tried it a few months ago, numpy was not yet working on M1 macs, but as of python 3.9.4, it installs normally using pyenv and pip.

I started a GitHub repo to hold the Excel spreadsheet and python port — I’ll be posting more ports to various frameworks. I like it as a simple example because it has conditionals, loops, arrays and is a pretty useful thing to know.

It’s also a good starting point for learning more programming. Excel is great, and there’s a lot you can do, but with the python version, I could add the following features.

- Instead of using constants for the various inputs (like market rate), use a lambda and define different ways the market could move rather than constant

- Do similar things with spending models in retirement, inflation, etc.

- Make it easier to have more lumpy spending/saving — meaning, assume aggressive spending in youth, then a period where you might have children and buying a house, then a house sale in the future, etc.

- Make it possible to show many more scenarios at once (like 30 historical market curves effect on your plan)

To be fair, all of this is very possible in Excel. It’s just a lot easier in python.

Write While True Episode 9: Deprivation

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

I don’t use a lot of social media, but if I don’t plan my time intentionally, I’ll find myself watching a lot of YouTube.

It’s not that I think that my life should be 100% dedicated to making new things or in solitary contemplation. But, there are times when I notice that level of output isn’t where I want it to be, and so I take a good look at how I am spending my time.

- SelfControl App

- Deep Work for Programmers and Self Control (from loufranco.com)

- The Artist’s Way [amazon affiliate link] by Julia Cameron

- Digital Minimalism [amazon affiliate link] by Cal Newport

- Bored and Brilliant [amazon affiliate link] by Manoush Zomorodi

- Note to Self podcast

- Bored and Brilliant challenge