I just opened a project I haven’t looked at in a few weeks because “holidays”. First thing I did was run tests, which didn’t run because I didn’t run them correctly. I looked at the README and it had no documentation for running tests.

In my book, Swimming in Tech Debt, I talk about this in the opening of “Chapter 8: Start with Tech Debt”. You can read this sample chapter and others by signing up to my list:

It opens:

You know the feeling. You sit down at your computer, ready to work on a feature story that you think will be fun. You sort of know what to do, and you know the area of code you need to change. You’re confident in your estimate that you can get it done today, and you’re looking forward to doing it.

You bring up the file, start reading … and then your heart sinks. “I don’t get how this works” or “this looks risky to change,” you think. You worry that if you make the changes that you think will work, you’ll break something else.

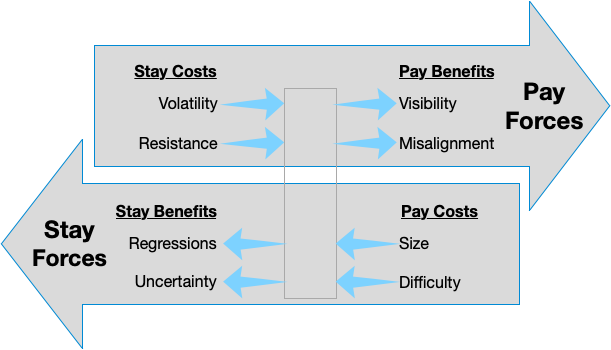

What you are feeling is resistance, which triggers you to procrastinate. You might do something semi-productive, like reading more code. Or you might ask for help (which is fine, but now you’ll need to wait). Maybe you reflexively go check Slack or email. Or worse, you might be so frustrated that you seek out an even less productive distraction.

The chapter is about immediately addressing this debt because you know it is affecting your productivity. It’s essentially free to do something now rather than working with the resistance.

So, following my own advice:

- I added text to the README explaining the project dev environment and how to run tests and get coverage data.

- Seeing the coverage data, I saw a file with 0 coverage and immediately prompted Copilot to write a test for one of the functions in it.

And that was enough to get warmed up to start doing what I was originally trying to do.