When I was in my early twenties, I got a call from a financial advisor asking if we could have a meeting to discuss my finances. I would say at that point (compared to now) I knew very little, but I did save a lot, maxed out my 401k, and didn’t have any debt. But, aside from the 401k, my money was just in a bank.

I agreed to have coffee with him.

Over the phone he took a bunch of information from me. My age, my salary, my savings, etc, and then at the meeting, he brought a small spiral bound book with a personalized plan.

I can tell you right now, that that plan was probably not good. He, almost certainly, was not a fiduciary, and the mutual funds he wanted to put me in probably had high fees.

One page of that book, though, changed my life.

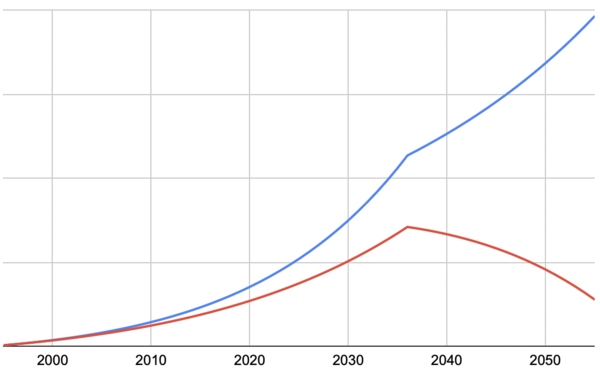

It was a line graph. The x-axis went from 1995 to 2055 or age 25 to 85. The y-value was my predicted net-worth. This was the result of using my expected salary growth, my savings rate, expense growth, my current net worth, inflation guesses, expected return, etc. You can find many such calculators on the web or do it yourself in Excel.

It was as you would imagine, an exponential growth curve that results from compound interest as long as returns and savings grow with respect to expenses and inflation.

The part that surprised me was that at 2035, when I would turn 65 and presumably retire, the curve had a noticeable notch, but still basically grew, but on a different exponential curve.

I asked how it could still go up after I retire, and he explained that at that point my investments would make more each year than I needed to spend, so they would keep growing.

I recreated the shape here.

In my mind, the red line was what I was going for—it’s not a bad outcome. He showed me that the blue line was not only possible, but actually, I was already headed there if I kept my savings rate. Most of the assumptions were fairly conservative. The only difference between those lines is expense growth (or, in other words, savings growth).

I honestly didn’t hear anything else he said that day. Look at what a difference it makes.

Assuming that you are not a stock-picking genius (spoiler alert: you’re not), and you are getting market returns from index funds, the only variable you control is savings rate. Of course, there are several components of savings rate, which I’ll talk about soon.