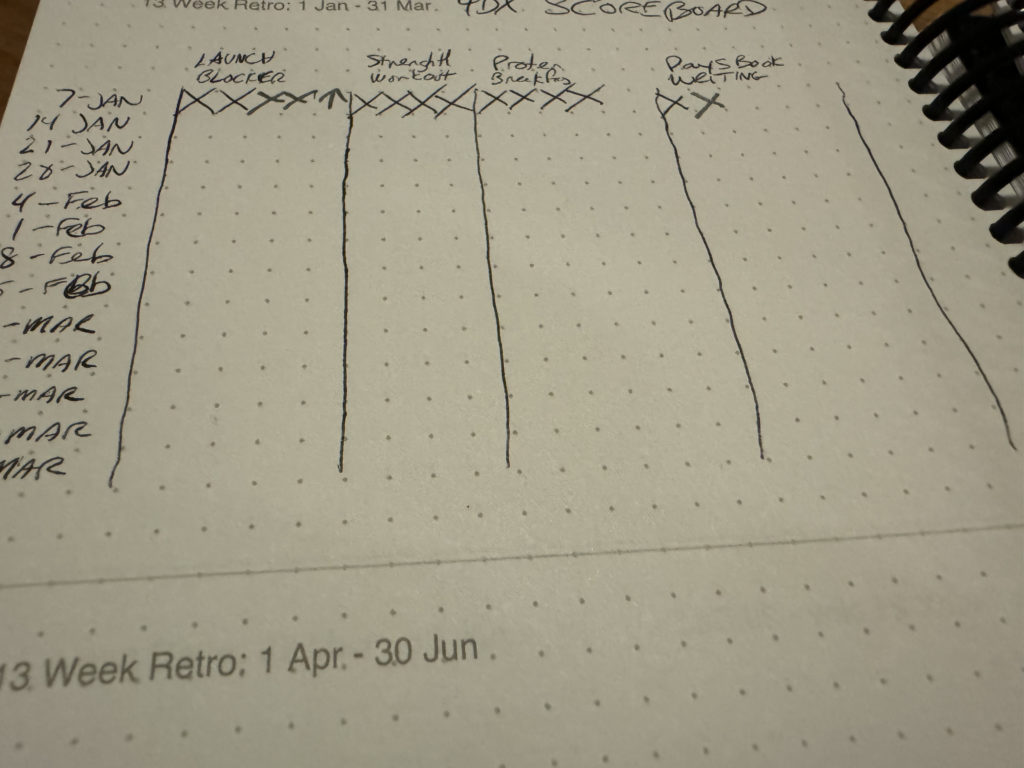

The second discipline of The Four Disciplines of Execution is to act on lead measures to accomplish the Wildly Important Goal (WIG). I defined my three WIGs yesterday

- Work: no launch blockers in the product by March 31, 2024

- Fitness: Go from 23% body fat to under 20% body fat by December 31, 2024.

- Personal Growth: Write two 50-page books and put them up for sale by the end of 2024.

For each of those, I have inherently expressed them in a way that defines a “lag” measure. On March 31, I will have launch blockers or not, but there will be nothing I can do on that day to change it. Each day, I will go on my scale and see my body fat %, but I will not really be able to do something that directly affects that in the short term.

4DX asks us to define lead measures that are things we can do right now that will lead to us accomplishing our lag measures. It measures our real-time activity, not the end result of the activity.

For work, it’s going to be time spent coding on launch blockers. I think I can get through the list if I spend 4+ coding hours on launch blockers per week. That might seem like too little—which is common in 4DX goals. You must accept that you still have all of the operational things you have to do. My partner and I are still experimenting, supporting early users, and possibly pivoting. I obviously need to work more than 4 hours per week on the project, but the majority of them are spent dealing with what the business needs today. My WIG is about how we get to the next level.

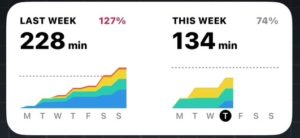

For fitness, I am accepting that my amount of body fat is very hard to lower (I have lowered it a lot, but have been stuck for a year), and so I am going to work on my amount of muscle mass, which means that I will do more strength training. My lead measure is to do 4 sessions of 10+ minute weight training workouts per week. It’s not 4+, because rest is important. It’s only 10 minutes, because I am working one body part fairly heavy and to failure. I am doing other workouts—these are in addition to what I am already doing, usually on the same day.

To support this, I am adding a secondary leading measure of eating a high-protein, lower carb breakfast 5 days per week. I usually eat oatmeal and fruit, which is perfectly sensible, but perhaps not supporting my WIG as well. I am not a low-carb person (quite the opposite), but I want to reduce this kind of carb. My new staple breakfast will be an egg substitute I make from soaked mung beans (similar to Just Egg) and tofu or tempeh. There is also a cafe near me that makes Just Egg omelets that I will have when I’m lazy. I might also use protein shakes, but rarely.

For my personal goal, since I am aiming for 50 page books, it might be tempting to have a weekly page count goal, but that won’t work for me because I write in drafts. Like my work goal, I think the easiest lead measure will be hours per week, so I will work on the book for at least one hour on five days per week. This will result in 5+ hours per week, but I think it’s important to have a daily practice of writing and not just do 5 hours in one day per week. It seems low, but I have other things I am doing besides this to maintain my level of output. I still want my blog and podcast to be going at the same time. The WIG is about what I can do to get to another level, not something I do instead of what I am doing now. In 6 months, that’s about 130 hours, which should be enough time to write and edit 50 pages.

You might disagree with my goals, and how I am trying to accomplish them. That’s ok, but that’s not the point. The point is that I am trying to accomplish big goals by concentrating on a process that is much more short-term and something I can definitely do (4DX calls this playing a winnable game). I will be checking in every 13 weeks to see if I am moving the lag measure, and adjust if not.