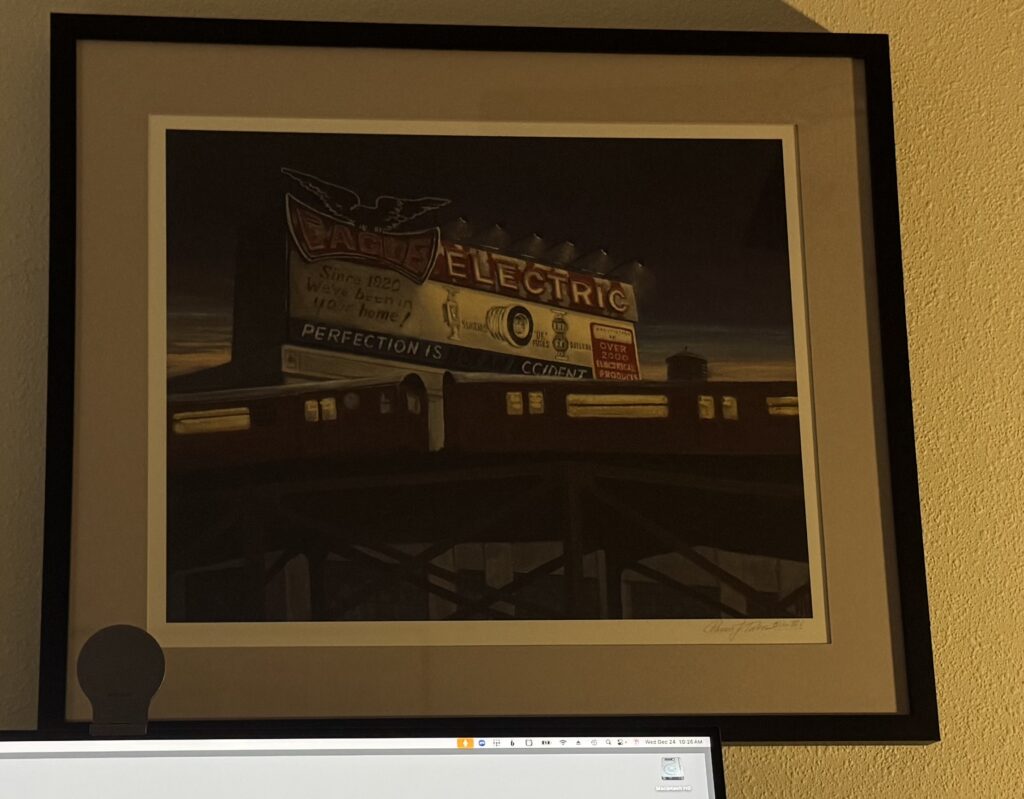

I took the Seven train into Manhattan often as a teenager. At Queensboro Plaza, I could see the billboard for Eagle Electric with their motto: “Perfection Is Not An Accident”. I think about it a lot. But, I probably have not seen it in person since the nineties. It’s gone now.

Until recently, I didn’t even remember the name of the company, just the motto. I wrote a little bit about this in my book, discussing the power of pithy, memorable value statements.

A year ago, I was at the New York Historical Society, and I saw a painting of it by Pamela Talese (you can see it on her collection of signs).

The feeling of nostalgia was overwhelming. I was instantly sent back to a conversation I had with my high school friends about the sign and its motto.

Luckily, she sells archival quality, Giclée prints of the nighttime one. I bought one and put it right over my monitor so I can see it when I work.

From Art & Fear [amazon affiliate link], I learned to use my personal imperfect work as a jumping off point to a new work. This painting, which shows a company striving for perfection, but coming up short with an imperfect sign, reminds me to keep trying.

It’s one example of Environment Hacking, and what I wrote about a few days ago in Use Motivation To Program Your Environment.