This is part of a series called Eight Questions to Ask About Your Tech Debt

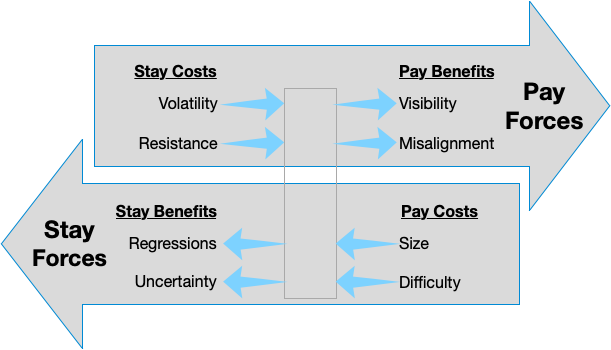

The main thing to keep in mind is this diagram (described in the introduction):

The next question we’ll cover is on Resistance: How hard is it to change this code if we don’t pay the debt?

I don’t like the financial metaphor of “debt” because it’s hard to use. When I am planning a project to fix a codebase’s problems, I never consider if the “debt” was caused by borrowing via a shortcut—it’s just not a useful attribute. The eight questions we’ve been going over are what I use instead. Among those, Resistance, is so important that is the source of my title, Swimming in Tech Debt. When I feel resistance while I am working, I try to do something, however small, right away.

The “while I am working” part is important, because that also indicates that Volatility is high (or at least pertinent). This code is hard to change, AND I need to change it right now. Part 2 of the book (which is available for free) lists all of the ways I use that feeling of resistance in the moment to clear some small piece of debt.

If you would like to relate this to the financial metaphor, I consider Resistance to be the size of the interest payment and Volatility to be the frequency of the payment. In many texts on tech debt, they might talk about an “interest rate”, but I don’t find that useful (how do you calculate it?). Instead, by using volatility and resistance, you get a trigger to make sure you avoid payments right when they are due, avoiding the charge. If you do this proportionately, fixing the problem can be zero cost. In many cases, it’s less than zero (you go faster by fixing the problem).

If you are planning a larger project (the subject of Part 3), then it becomes important to make an estimate of Volatility and Resistance to estimate the cost of doing nothing. If the cost of doing nothing is high, then the Pay Force will also be high.

Estimate Resistance with Code Metrics

Resistance is an attribute of the code, so it is possible to estimate it directly by analyzing the code. This is going to be the subject of my talk at STARWEST in a couple of weeks. If you are interested in that and have time, I would love to show you my slides and get your feedback (reply to this email).

My main way of surfacing resistance is by measuring code coverage in conjunction with complexity. Code that is both undertested and complex is risky to change. I showed the VSCode extensions I use to do this in Chapter 9 (available for free). I also recently vibe coded a CLI that can show me the most risky functions in my code using ESLint (for complexity) and JSTest (for coverage). I documented that here: Finding Functions That Are Risky To Change.

But these aren’t the only ways. You can use linters, compiler warnings, coupling reports, and other tools to give you an indication of how hard it will be to change parts of your code. They often can point to specific fixes, and with AI, maybe even help you address it.

Next: #7 Regressions