This is part of a series called Eight Questions to Ask About Your Tech Debt, which is based on content in Swimming in Tech Debt.

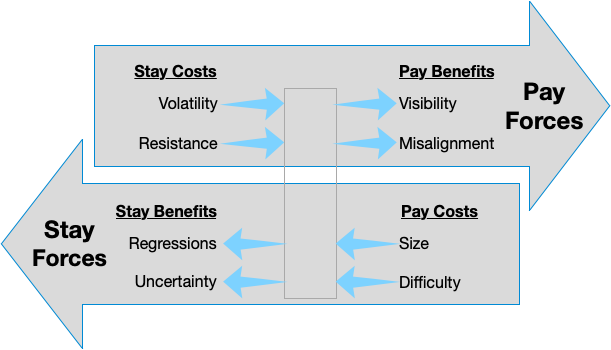

The main thing to keep in mind is this diagram (described in the introduction):

The first question we’ll cover is on Visibility: If this debt were paid, how visible would it be outside of engineering?

To me tech debt describes code that resists changes that you want to make. It’s a description of the code. It lowers developer productivity. It’s inherently internal and invisible to stakeholders. But, some tech debt, when addressed, incidentally fixes a bunch of bugs, security issues, or may even deliver a new desired feature. All of these effects make the tech debt more relevant to others outside of engineering. They can’t see the code, but they see issues fixed in the application.

Let me give you two examples. The first is something highly visible and the second is invisible.

A High Visibility Example

I worked on the iOS app at Trello and our Markdown renderer didn’t match the one used in the web version. This was caused by each of our teams independently using different third-party libraries and the fact that Markdown is poorly specified. We had a stream of support cases telling us that this wasn’t acceptable to customers.

There were two ways to address this problem. We could have gone one-by-one with each bug and try to hack a fix inside of our parser. Most likely, we would have needed to fork it first, so that we could change its internals.

The second way, which addressed its debt, would be to rewrite it as a line-by-line port of the web version. Doing that correctly would incidentally resolve all of the open bugs. That is what a highly visible tech debt project looks like — you are changing the code to be easier to change in the ways you want to, but the effect is visible to customers who get benefits too.

In my book, I describe visibility as having levels that extend outwards from engineering, to close non-engineering peers (QA, Product), to Sales and Marketing, to Support, and finally to customers. The more visible the effect is to customers or peers that interact with them, the higher I would score the Visibility dimension. The visible change must also be desirable to them.

A Low Visibility Example

The second example happened a few companies I worked at. When you are writing in a compiled language (like C, C++, Objective-C, or Swift), you will often have warnings (in addition to errors). If you don’t fix those problems, then, over time, you start to ignore new ones. The list of warnings will grow and become useless.

But warnings are sometimes important and indicate a real problem. Generally, I would recommend that you fix all of them, but if you have a lot, then it might take some time, which warrants planning.

Fixing them would mostly affect engineers though. It’s possible that fixing one incidentally fixes a bug, but we don’t know that, and if we did know of a bug, we could address just that issue without fixing all of the warnings. I would score Visibility on a problem like this as low. Another common is example of a low visibility issue is having low unit-test coverage.

But, even completely invisible problems can be made visible. On one of my teams, we had very slow build times, but one of my colleagues collected daily build data from our IDEs and made a dashboard. This made it visible to our manager and their managers, which is better than nothing. This would not score as high as a customer issue, but it’s more than just completely internal to our team.

Watch out if Visibility is the only Pay Force

Visibility works with Volatility, Resistance, and Misalignment to drive the Pay Force. We’ll go through each of those in the next few days. One thing to watch out for is if Visibility is the only one driving the Pay Force. If so, this is probably not really a tech debt problem—it’s just a regular feature or bug. I would projects like this at the discretion of your Product Manager or Product Owner.

Next: #2 Misalignment